Processing the SVO and OVS Word Order in Croatian: The Role of Prominence Features in Comprehension and Acceptability

Irina Masnikosa and Anita Peti-Stantić (University of Zagreb)

In line with Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Schlesewsky’s (2009) assumption of prominence-based argument processing of transitive structures, the present study is aimed at experimentally examining the prominence hierarchy in Croatian. Croatian is a language with flexible word order, case-marking, gender-marking and animacy-marking. However, the canonical order is considered to be SVO (Greenberg 1963) . While the incremental argument interpretation in transitive sentences in Croatian predominantly relies on case marking (MacWhinney and Bates, 1989), case syncretism can help differentiate the role morpho-syntactic, semantic and information-structural principles each play in word ordering. We used temporarily ambiguous input to test the effects of (i) morphological marking vs. sentential position, (ii) animacy, and (iii) givenness in processing SVO and OVS orders.

Methods and Analysis

We have conducted three online experiments using the web-based platform IbexFarm (Drummond, 2011. Each trial consisted of a self-paced reading task (word-by-word segmentation) followed by an acceptability judgment task. The self-paced reading task explored to what extent speakers use sentential position, animacy and givenness to incrementally assign arguments, while the acceptability judgment task was used to test the overall preference for (i) S>O, (ii) animate > inanimate and (iii) given information > new information. We collected the measures for (i) sentence ratings on a 1-5 Likert scale, (ii) reaction times for acceptability judgments and (iii) reading times for individual words. The analyses were carried out in R (R Core Team, 2021) using (i) cumulative link mixed models for acceptability rating data and (ii) generalized linear mixed models for reaction time data. Reading times data longer than 3000 ms and shorter than 100 ms were excluded from the analysis.

Experiment 1: Subject before Object

Following Bornkessel and Schlesewsky’s (2006) Minimality principle, we assume that, in the absence of morphological cues, the processing system assigns minimal structure, i.e. the canonical word order. In the first experiment, we test the canonicity of S > O order capitalizing on the syncretism for Nom/subject and Acc/object masculine nouns (1a,b). We predicted the initial interpretation of the first NP as subject, leading to (i) lower ratings and (ii) reanalysis (i.e. longer reading times) when the information in the disambiguating region (lexical verb) is incompatible with the S > O reading (Table 1, condition 4).

Participants: n = 40 (M = 9), mean age = 22.75

Table 1

Exp. 1: Factors, conditions and sample items

| F1: Argument order [Subject – Object: SO; Object – Subject: OS]

F2: Ambiguity [Ambiguous: AMB; Unambiguous: UNAMB] |

|

| Condition | Example |

| (1)

SO_UNAMB

|

Plaht-a je pokri-la fotelj-u.

sheet-F.SG.NOM AUX.3SG cover-PTCP.F.SG armchair-F.SG.ACC “The sheet covered the armchair.“ |

| (2)

OS_UNAMB

|

Fotelj-u je pokrila plaht-a.

Armchair-F.SG.ACC AUX.3SG cover-PTCP.F.SG sheet-F.SG.NOM “The sheet covered the armchair.“ |

| (3)

SO_AMB

|

Vjetar je otpuhao brod-ić.

wind.M.SG.NOM AUX.3SG blow.away-PTCP.M.SG boat-DIM.M.SG.ACC “The wind blew away the boat. “ |

| (4)

OS_AMB

|

Brod-ić je otpuha-o vjetar.

boat-DIM.M.SG.ACC AUX.3SG blow.away-PTCP.M.SG wind.M.SG.NOM “The wind blew away the boat. ” / #”The boat blew away the wind.“ |

Results:

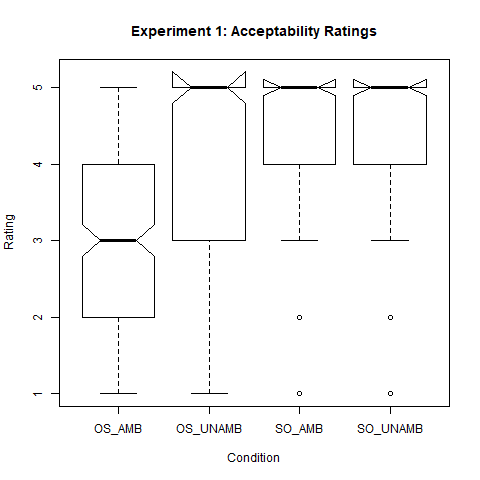

Fig 1

Exp. 1: Acceptability ratings per condition

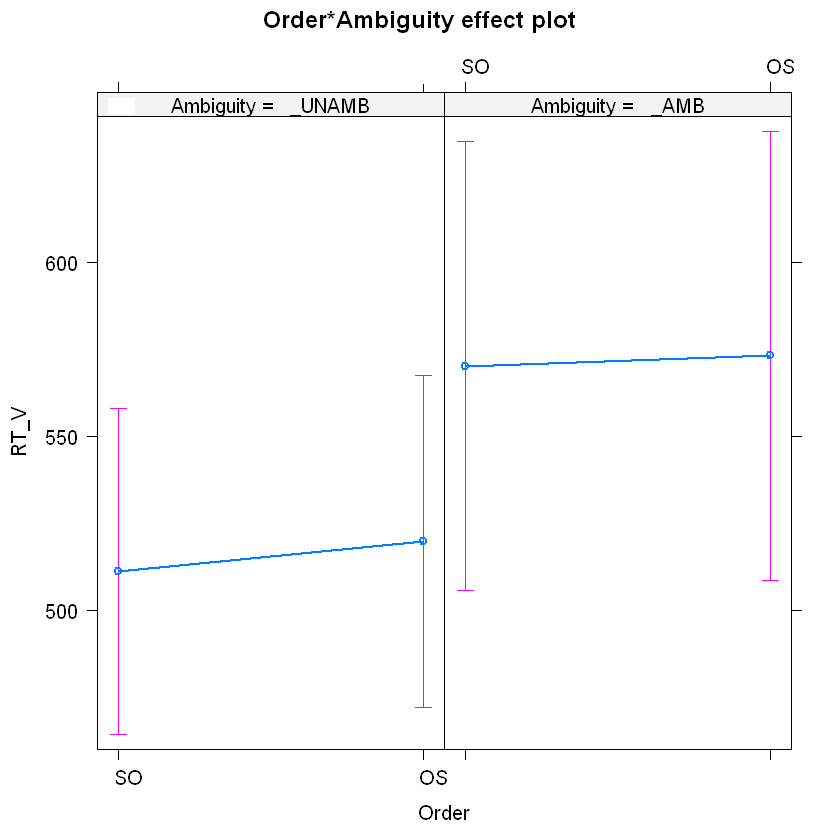

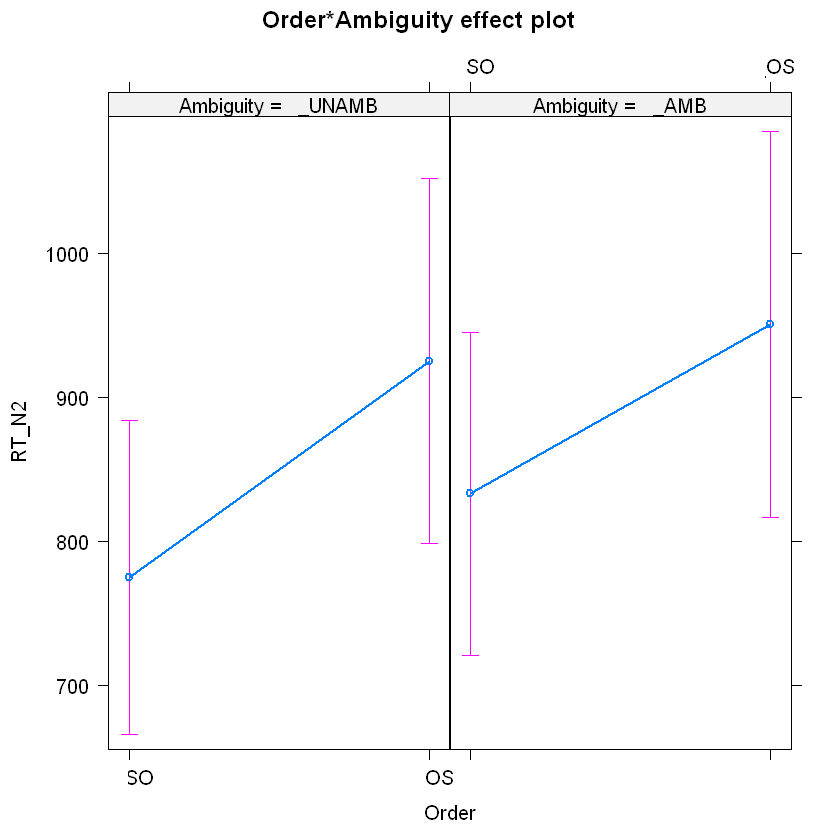

With the SO_UNAMB condition set as the intercept, the analysis of acceptability ratings showed significant effects of (i) argument order (estimate = -2.0899; std.error = ; z = 0.5463; p < .001), and (ii) interaction of argument order and ambiguity (estimate = -1.7140, std.error = 0.6533; z = -2.624, p < .01). The results suggest that the absence of the morphological cues is penalized only in the OVS word order, indicating the independent preference for SVO. Analysis of the reading times for critical segment (verb) shows a significant effect of ambiguity (estimate = 59.093, std error: 20.479, t =-2.006, p < .01, , i.e. faster reading times for conditions with morphologically unambiguous stimuli, while the analysis of the reading times for the following word (verb+1) shows a significant effect of argument order (estimate = 150.17, std error = 27.09, t =-5.544, p < .001), i.e. faster reading times for SVO conditions.

Fig 2 Fig 3

Exp. 1: Effect plot for RT/ms in critical segment (verb) Exp.1: Effect plot for RT/ms in segment verb+1

Experiment 2: Animate before Inanimate

In the second experiment, we tested the role of animacy in argument assignment for temporarily ambiguous NPs. Based on previous research (Mak et al., 2006 for English; Jackson and Roberts, 2010 for Dutch), we predicted the preference for animate subjects, leading to (i) lower ratings and (ii) slower reading times when the subject in canonical position is inanimate (Table 2, condition 4 in comparison to condition 1). Considering the penalty for the morphologically unmarked OVS order shown in Experiment 1, the effect of argument order was expected as well.

Participants: n = 40 (M = 10), mean age = 22.34

Table 2

Exp. 2: Factors, conditions and sample items

| F1: Argument order [Subject – Object: SO; Object – Subject: OS]

F2: Animacy order [Animate – Inanimate: AI; Inanimate – Animate: IA] |

|

| Condition

|

Example |

| (1)

SO_AI

|

Policajk-e su ugledale novčanic-e.

policewoman-F.PL.NOM AUX.3PL see.PTCP.F.PL banknote-F.PL.ACC “The policewomen saw the banknotes.“ |

| (2)

OS_AI

|

Policajk-e su začudile novčanic-e.

policewoman-F.PL.ACC AUX.3PL astonish.PTCP.F.PL banknote-F.PL.NOM ‘The banknotes astonished the policewomen.”/# ‘The policewomen astonished the banknotes.” |

| (3)

OS_IA

|

Novčanic-e su ugledale policajk-e.

banknote-F.PL,ACC AUX.3PL see-PTCP.F.PL policewoman-F.PL.NOM ‘The policewomen saw the banknotes. “/# “The banknotes saw the policewomen.” |

| (4)

SO_IA

|

Novčanic-e su začudile policajk-e.

banknote-F.PL.NOM AUX.3PL astonish- PTCP.F.PL policewoman-F.PL.ACC ‘The banknotes astonished the policewomen.“ |

Results:

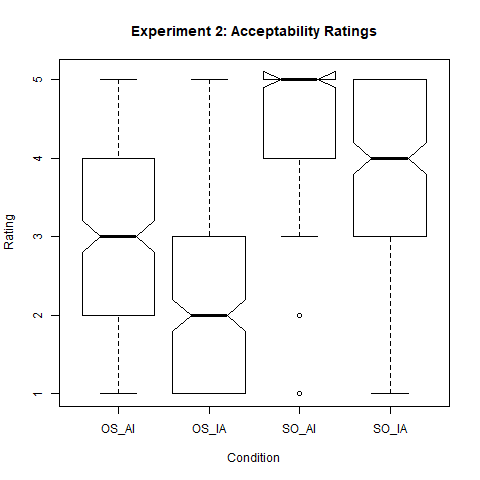

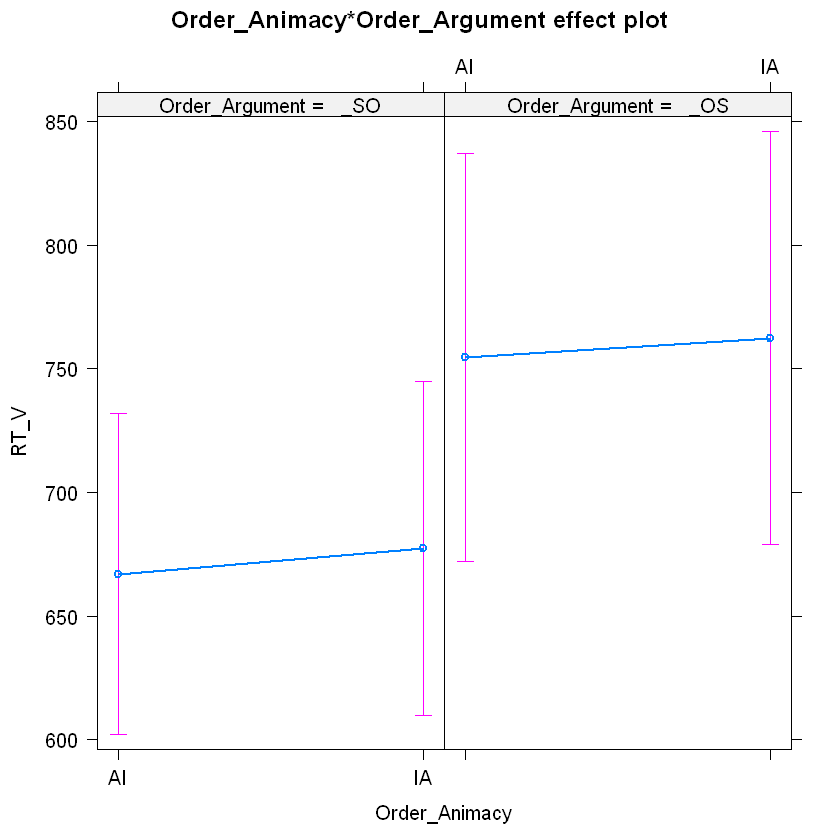

Fig 4

Exp. 2: Acceptability ratings per condition

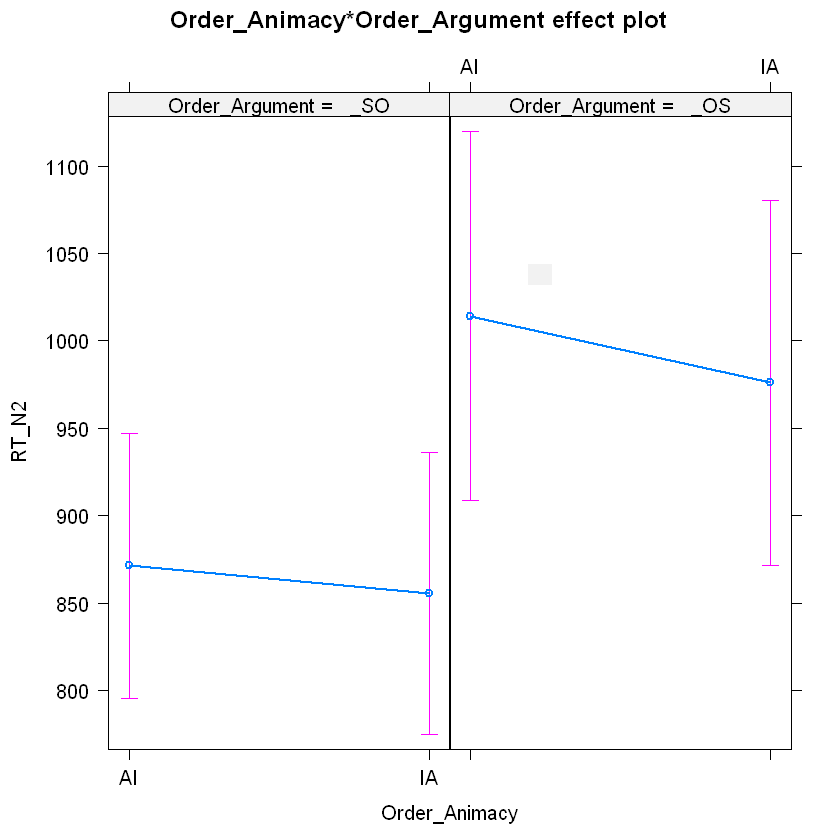

With the SO_AI condition set as the intercept, the analysis of acceptability ratings shows significant effects of both (i) animacy order (estimate = -1.5596, std. error = 0.2848, z = -5.476 , p < .001) and (ii) argument order (estimate = -3.7854 , std. error = 0.3893, z = -9.724, p < .001). In addition to the predicted decline of ratings for inanimate subjects in the SO condition, sentences with the animate nouns in the initial position received higher ratings even in the dispreferred OVS order, which indicates the presence of the independent principle of animacy ordering. The analysis of the reading times for both the lexical verb and the following word showed significant effects of argument order (verb: estimate = 87.684, std. error = 24.183 , t = – 3.626, p < .001; verb+1: estimate = 142.86, std. error = 43.36 , t = 3.295, p < .001). However, no significant fixed effect of animacy was found.

Fig 5 Fig 6

Exp. 2: Effect plot for RT/ms in critical segment (verb) Exp. 2: Effect plot for RT/ms in segment verb+1

Experiment 3: Given before New

In Experiment 3, we used ambiguous experimental items from Experiment 1 to test the preference for given information to precede new (Kučerova, 2007), a generalization that has been challenged in Slavic (Šimík and Wierzba, 2017). The given > new preference was expected to (i) license the OVS word order and (ii) facilitate disambiguation when the object is given in the previous context (Table 3, condition 2 in comparison to condition 4).

Participants: n = 37(M = 13), mean age = 22.75

Table 3

Exp 3: Factors, conditions and sample items

| F1: Argument order [Subject – Object: SO; Object – Subject: OS]

F2: Givenness [Subject Given: SG; Object Given: OG] |

|

| Context 1 | Htjeli smo uzeti brodić i otploviti na more, ali nismo mogli. (We wanted to take the boat out to sea, but we couldn’t.) |

| Condition | Example |

| (1)

SO_OG |

Vjetar je otpuha-o brod-ić.

wind.M.SG.NOM AUX.3SG blow.away-PTCP.M.SG boat-DIM.M.SG.ACC “The wind blew away the boat. “ |

| (2)

OS_OG

|

Brod-ić je otpuha-o vjetar.

boat-DIM.SG.M.ACC AUX.3SG blow.away-PTCP.M.SG wind.SG.M.NOM “The wind blew away the boat. ” / #”The boat blew away the wind.“ |

| Context 2 | Zapuhao je snažan vjetar. (A strong wind started to blow.) |

| Condition | Example |

| (3)

SO_SG |

Vjetar je otpuha-o brod-ić.

wind.M.SG.NOM AUX.3SG blow.away-PTCP.M.SG boat-DIM.M.SG.ACC “The wind blew away the boat. “ |

| (4)

OS_SG

|

Brod-ić je otpuha-o vjetar.

boat-DIM.M.SG.ACC AUX.3SG blow.away-PTCP.M.SG wind.M.SG.NOM “The wind blew away the boat. ” / #”The boat blew away the wind.“ |

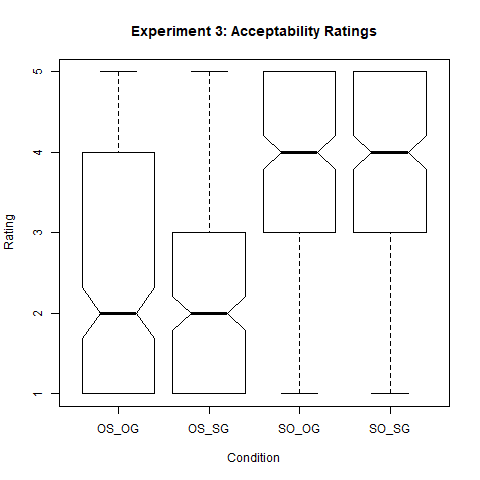

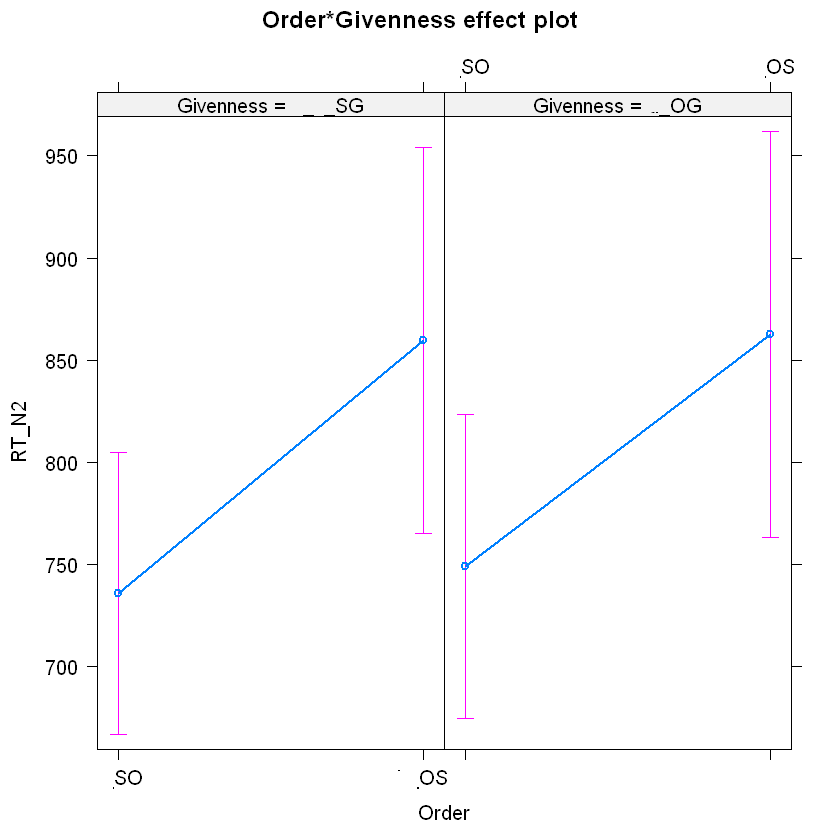

Results:

Fig 7

Exp. 3: Acceptability ratings per conditions

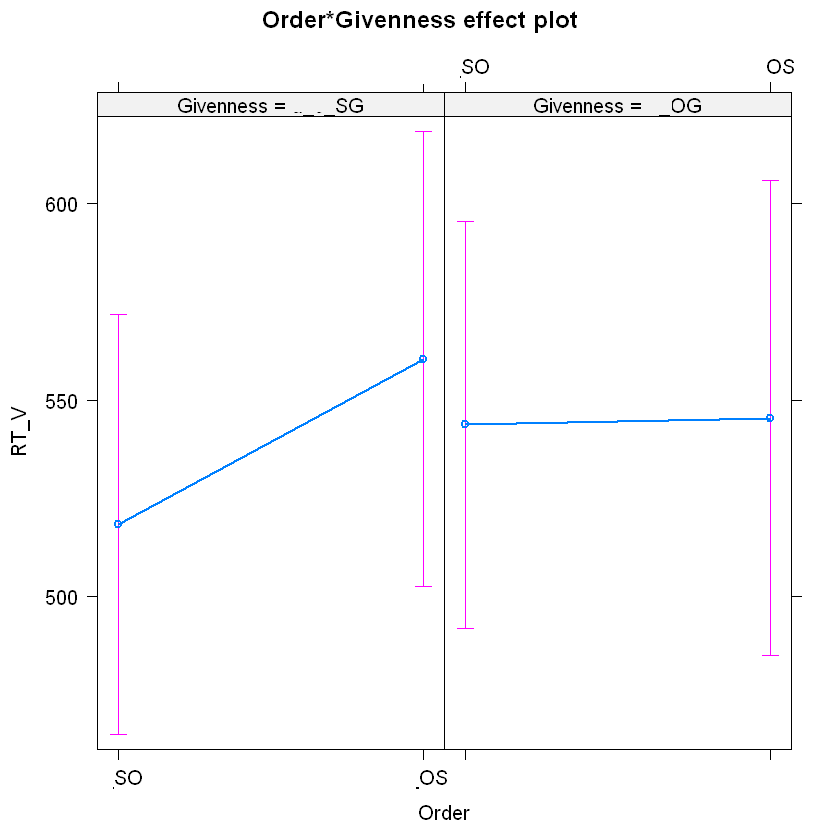

The results did not provide evidence for the given > new preference. With the SO_SG condition set as the intercept, the analysis of acceptability ratings only shows a significant effect of the argument order (estimate = -3.1398, std. error = 0.4433, z = -7.082, p < .001). In addition, the analysis of the reading times for both verb and the following word yielded a significant effect of argument order (verb: estimate = 42.23, std.error = 20.36, t = 2.074,

p < .05; verb+1: estimate = 123.64, std.error= 30.94, t = 3.996, p < .001).

Fig 8 Fig 8

Exp. 3: Effect plot for RT/ms in critical segment (verb) Exp. 3. Effect plot for RT/ms in segment verb+1

Discussion and Conclusion

While the results of the first experiment confirm case-marking to be a cue for incremental argument interpretation in Croatian, the present study provides evidence that the sentential position of argument plays a prominent role in the interpretation of transitive sentences, even when the morphological cues are available. The canonicity of SVO word order is supported not only by the results of the acceptability judgment tasks but also by the self-paced reading tasks. The results from Experiment 2 indicate that the semantic feature of animacy has an impact upon the assessment of role prototypicality, but should be placed lower on the prominence scale for Croatian. On the other hand, the information-structural feature of givenness did not significantly affect the acceptability or reading times of sentences with the dispreferred OVS word order. However, this may be due to the difficulty of capturing the potential information-structural effects with the current experimental design, therefore we argue that their role in word ordering in Croatian should be further investigated in a production task.

References:

Bornkessel, I., & Schlesewsky, M. (2006). The extended argument dependency model: A neurocognitive approach to sentence comprehension across languages. Psychological Review, 113(4), 787–821. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.4.787

Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, I., & Schlesewsky, M. (2009). The Role of Prominence Information in the Real-Time Comprehension of Transitive Constructions: A Cross-Linguistic Approach: Prominence-Driven Sentence Processing. Language and Linguistics Compass, 3(1), 19–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00099.x

Drummond, A. (2011). IBEX Farm [Computer software]. http://spellout.net/ibexfarm/

Greenberg, J. H. (1963). Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. Universals of language. Universals of Grammar, 73-113.

Jackson, C. N., & Roberts, L. (2010). Animacy affects the processing of subject–object ambiguities in the second language: Evidence from self-paced reading with German second language learners of Dutch. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31(4), 671-691. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716410000196

Kučerová, I. (2007). The Syntax of Givenness. MIT.

MacWhinney, B., & Bates, E. (Eds.). (1989). The Crosslinguistic study of sentence processing. Cambridge University Press.

Mak, W., Vonk, W., & Schriefers, H. (2006). Animacy in processing relative clauses: The hikers that rocks crush. Journal of Memory and Language, 54(4), 466–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2006.01.001

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Šimík, R., & Wierzba, M. (2017). Expression of information structure in West Slavic: Modeling the impact of prosodic and word-order factors. Language, 93(3), 671–709. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2017.0040

171 total views, 1 views today

This post is also available in:  Hrvatski (Croatian)

Hrvatski (Croatian)